Chapter I. Facing the moral vexation of

sustainability: the case for an ecological economic overhaul

"It is not from the benevolence of the

butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but

from their regard to their own interest."

– Adam Smith, The

Wealth of Nations, 1776

"[the laws of thermodynamics] control, in

the last resort, the rise and fall of political systems, the

freedom or bondage of nations, the movements of commerce and

industry, the origins of wealth and poverty, and the general

physical welfare of the race."

-Frederick Soddy, Matter

and Energy, 1912

"I am saddened that it is politically

inconvenient to acknowledge what everyone knows: the Iraq war is

largely about oil..."

– Alan Greenspan, The

Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World, 2007

Denial of a crisis begins with the denial

of its ethical or moral vexations. No greater

crisis has ever faced humanity than the current human

population over the natural carrying capacity of the planet,

combined with peak

oil. But the mere suggestion that peak oil is the

primary motivation of our foreign policy evokes conflict in the

polite society behind enemy lines, leaves your patriotism

impugned, and is "politically inconvenient" for our elected and

appointed officials. The level of denial of our energy motives is

astounding, a performance of mesmerizing dance steps and

pirouettes. Any presentation of the evidence, summary of

historical observations,

Oil Cat-and-Mouse Bookends, a picture and its 1000 words:

Donald Rumsfeld, serving as a special envoy for President

Ronald Reagan, shakes hands with Saddam Hussein in Baghdad in

December, 1983 during the height of the 1980-1988

Iran-Iraq war, a war started in major part by the Sunni

leader's fear of an Iranian inspired Shia insurgency. "Rumsfeld met

with Saddam, and the two discussed regional issues of mutual

interest, shared enmity toward Iran and Syria..." ( http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB82/

) Despite Iraq's use of chemical weapons in the war, the U.S.

renewed diplomatic ties with Iraq by the end of 1984. The

Iran-Contra affair, beginning in November, 1986, would later

reveal that the U.S. was involved in secret covert arms sales to

Iran at the same time it was overtly supporting Iraq. The

focus of the controversy was centered on the illegal shipment of

arms to the Nicaraguan Contras in violation of the Boland

Amendments, and that the funds for the arms were raised by

selling weapons to Iran. The fact that the US was thus

supporting both sides of the Iran-Iraq war went largely unnoted

by the US press. The Iran-Iraq war ended in 1988 in

stalemate, resulting in hundreds of thousands of casualties for

both sides, many from weaponless

combatants participating in human

wave assaults on machine gun positions. Two years

later, on August 2, 1990 Hussein invaded Kuwait.

Transcripts of a meeting before the invasion, on July 25,

1990, between Saddam Hussein and U.S. Ambassador to Iraq,

April

Glaspie, have been interpreted as having given tacit US

approval for the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. But

instead George H.W. Bush began the Gulf War to remove Saddam

Hussein from Kuwait on February 24, 1991. On February 26

and 27, the US attacked retreating Iraqi forces on what became

known as the Highway of

Death estimated to have killed "tens of thousands."

The war strengthened U.S. alliances with Saudi Arabia and

Kuwait, alliances maintained by leaving Hussein as a threat

in power in Iraq, a move which also served to use Iraq as a buffer

for Kuwait-and-Saudi Arabia against Iran. Though 15 of the

supposed 19 hijackers on 911 were Saudi Shiites, the Sunni Saddam Hussein was

accused of aiding the terrorists as part of a deliberate

fabrication to justify George W. Bush's Iraq War.

Donald Rumsfeld served as George W. Bush's defense

secretary, orchestrating and promoting Bush's Iraq War to oust

Saddam Hussein from Iraq, which began in March, 2003.

or dialectic of the facts alluding to energy

motives are dismissed as mere political opinion. The

significance of Alan Greenspan's Iraq concession was not the

admission of reality, but rather that reality had gained some

credibility having been "acknowledged" by a retired chief

economist. Why is legitimacy only granted by economics? Why is

audacity only granted by retirement? Why doesn't anyone in

polite society really discuss the war at all? Perhaps now we can

begin a more fruitful discussion. If "everyone knows," why is

reality "politically inconvenient?"

We have an ethical mystery to solve,

rooted in energy economics, complete with a cover-up, or at least

an evasiveness characteristic of crime. Former Manson prosecutor

Vincent Bugliosi, author of None Dare

Call It Treason, will tell you that, although motive only

provides circumstantial evidence, comparable in value to that of

so many conspiracy theories, establishing motive is essential to

making a case. Money may not be one's primary value or pursuit in

life, but thus springs forth our motives, at least according to

market-based economic theory. In his Harpers article The Oil We

Eat, Richard Manning set out to solve an energy mystery, to

find a concentration of energy wealth. Noting that Cheney had

equated money with energy, he invoked the journalist's rule to

"follow the money." Following the energy, his path led to our farm

fields. Forty percent (40%) of the world's population is fed from

three main grains, fertilized with ammonia produced from one

percent (1%) of the world's total energy production. In addition

to being essential to the economy at large, it turns out energy

resources are eaten, quite literally, and Manning had followed our

food chain back to Iraq.

With the price of gasoline doubled since

2000, peak oil awareness is growing, a reason to be cautiously

optimistic that we can at least have frank discussions about

energy. The "oil glut" of the '80's and '90's gave rise to

gluttonous attitudes that prevented any serious discussion of

conserving or weaning from fossil fuels. But unfortunately even

today the focus of the peak oil debate–will it be next year, 10

years, or 50 years from now, or was it really in 2004?– is a

canard. Hubbert's

peak oil curves presented in the common debate plot annual

production of oil, in billions of barrels produced, through time

in years. Depending on the bias of the analysis, the curve is

either leveling off, but still surpassing historic levels, or has

just passed its peak where world production will never meet

historic levels. An honest discussion of the debate, though, would

at least acknowledge what Olduvai

theorist Richard Duncan points out: oil production per world

human population peaked in 1979. That is to say, the most energy

produced per person peaked 30 years ago and has been declining

ever since, due to the combination of explosive world population

growth and leveling production combined. The rest, as they say, is

politics. In the context of oil per capita, the fact that the Pentagon is the

single largest purchaser of petroleum in the world goes a

long way in explaining our history in the Middle East, our

involvement in the current wars there, and our concerns expressed

politically over what effect China's new economy, coupled with its

population, will have on our energy security. Extreme self

delusion is required to deny our true intentions in the Middle

East, but examples of the prerequisite moral backflips are hardly

uncommon. The political inconvenience is in having to admit moral

vexation.

Manning's mystery to solve was to find

the source of a concentration of great wealth, the energy wealth

invested in our food. He gave us a glimpse, a first clue that

there is a modern moral vexation in sustainability. As essential

as a read can be, his article only followed the first part of the

story, the first law of thermodynamics, that energy is neither

created or destroyed and thus can be traced like a currency.

Though Manning very definitely enumerated the environmental

ramifications of industrial agriculture, unfortunately there is a

second part of the story, another energy connection to

sustainability that is even bigger. The moral vexation that is the

result of solving Manning's mystery thus grows ever larger. This

second part of the story leaves a different mystery to solve, the

dispersal of great wealth. Why do we have the colossal scale of

recent bankruptcies?

Not to excuse greed, but greed is not why

we're so deep in the red. Greed merely involves the concentration

of wealth in certain pockets at the expense of others. The debt

problem is more systemic, and as we'll see throughout this

article, its roots lie in the second part of the energy story, a

sequel called entropy. Entropy is the fundamental concept of the

second law of thermodynamics describing the dispersal of energy.

Cheney's equation is correct. Money and energy are so

fundamentally linked, in fact, that if you include entropy while

tracing the energy currency through our economic system, you'll go

a long way to explaining the cause of our national debt: energy is

dissipated permanently, no matter how much you might fight for it,

and thus so is money. Entropy happens.

We are now in the process of

restructuring our economy. Can we finally address entropy? Can we

at least recognize this energy source of our debt and structure

our economy in such a way to make it sustainable without vexation?

The adjective "sustainable" has long been defined and understood

to be our goal economically, but the new noun-form,

"sustainability" – still not listed in many dictionaries and still

not recognized by Microsoft Word's spell-checker – conjures an

environmental agenda. Isn't environmental consideration a luxury

we can't afford, especially now? Or as some circles might

pejoratively pose the question, isn't "sustainability" just a

"politically correct" buzzword? A noted environmentalist Lester Brown did, in

fact, coin the term sustainability in 1981, but his definition

said nothing about the environment: "[the ability to meet] the

needs of the present without compromising the ability of future

generations to meet their own needs." True, sustainability is a

term increasingly used to justify environmental action. But

Brown's definition merely addresses an ethics towards future

generations. Is our environment in crisis, our livelihood

currently not sustainable, as the imperative nature of its goal

implies? Is Al Gore correct that economic sustainability is

contingent upon environmental sustainability?

What is essential to sustain both the

economy and the environment is energy. What is generally not

understood, though occasionally illuminated by articles like

Manning's, is that we

are above the natural carrying capacity of the planet for humans.

Thus the ecosystems we rely on to sustain life are intrinsically

requiring more and more of our energy resources to be maintained,

including resources that had been traditionally reserved for our

economy. At least part of the dispersal of wealth, alluded to

above, goes into environmental action. Until relatively recently,

the energy needed for sustainability has been kept paced naturally

by solar energy, and thus largely taken for granted. As the energy

required to sustain world population takes an ever increasing

amount from what was historically used for our economy, it is no

wonder that environmental issues are presented politically as a

choice, or at least as an exercise in striking a balance between

the economy on one hand and the environment on the other. The

reality, of course, is that both need to be maintained in order

for humanity to be sustained. The environmental urgency is

generally not appreciated as much as the economic, however.

The vast majority of the world's

population has no idea that it exceeds the planet's carrying

capacity for its own numbers, a condition fleetingly possible only

through industrial consumption of currently available energy

resources, especially for agriculture. Of course the consumption

of these energy resources is disparate by culture and lifestyle. Ecological

footprint analysis attempts to sum all of the resources

consumed in a given lifestyle, energy being perhaps a major but

not exclusive resource, and has gone a long way in generating

awareness of these disparities, which in turn has greatly

increased "green consciousness." But the more common effect on the

populace is to induce a sense of guilt which inspires no action.

We may suffer an increasing sense of creeping malaise as we hear

on the radio each new environmental crisis or resource scarcity

issue while we drive to pick up our new plasma T.V., but no

action. In fact the guilt can inspire a kind of ameliorating, or

even backlash, consumerism.

The environmental community must admit

and come to terms with economic motives. Environmental

preservationist's hold that nature's value is self evident,

quoting John Muir, "Everybody needs beauty as well as bread,

places to play in and pray in, where nature may heal and give

strength to body and soul." As hard as it is to believe, this

value system is not universal, and this valuation of nature as

priceless is left out of even modern economics. The science of

ecology is more quantifiable, and thus ecologists are making more

practical inroads. Ecological footprint analysis has generated

awareness of the value of the natural resources we take for

granted. But there will be no action, no change of behavior,

unless that value is embedded into our economy. Energy presents a

way to embed that value. All of the renewable resources we consume

can be generated with energy at some time scale, perhaps most with

time or energy too excessive to be feasible, but at least

providing a basis to measure our economy. The environmental

community generally scorns a consumerist approach, thus the

resistance to cap-and-trade programs that "commodify" the

environment. But can there be any other way to economically reward

prevention of pollution or conservation of resources?

The Iroquois Indians based their economy

on a currency of clam shell beads. Certain pre-Columbian

civilizations used chocolate, feudal Germany used land. We use to

base our economic system on silver, then silver and gold, then

gold alone, and now by fiat.

Clam shells, chocolate, land, silver, gold, and Federal

Reserve checks to the government all have their

value–especially chocolate–but isn't it time for our economic

system to be based on something universally sound, the physical

unit of energy, a different jewel spelled J-o-u-l-e? Most would

argue that the modern economy is too complex to ever accept a

commodity-based currency again. But is energy only a commodity?

The idea to establish an energy currency

is nothing new. Energy is central to what an economic system

attempts to organize: the ability to perform work, and the

inherent value of goods and services resulting from that work. M.K. Hubbert of

peak oil fame was a founder of the technocracy movement,

and in 1940 proposed to replace money with energy certificates

limited to the energy invested in GDP, distributing the

certificates pro rata in a non-market economy. Frederick Soddy,

winner of the 1921 Nobel chemistry prize for determining the

helium chemical composition of alpha nuclear radiation, was one of

the technocracy movement's champions, and suggested that energy

and its technocrats would replace human labor. A non-market

economics run by a technical elite was as suspect then as it is

now. "Hubbert's membership of the Technocracy movement was

investigated in 1943 by his employers, the Board of Economic

Warfare, who may have regarded it (not entirely unreasonably) as

a form of communism - though engineers desiring political

control didn't seem to do much better in the Soviet Union

either." (The

Oil Drum, 2008) At the same time, the technocratic elite

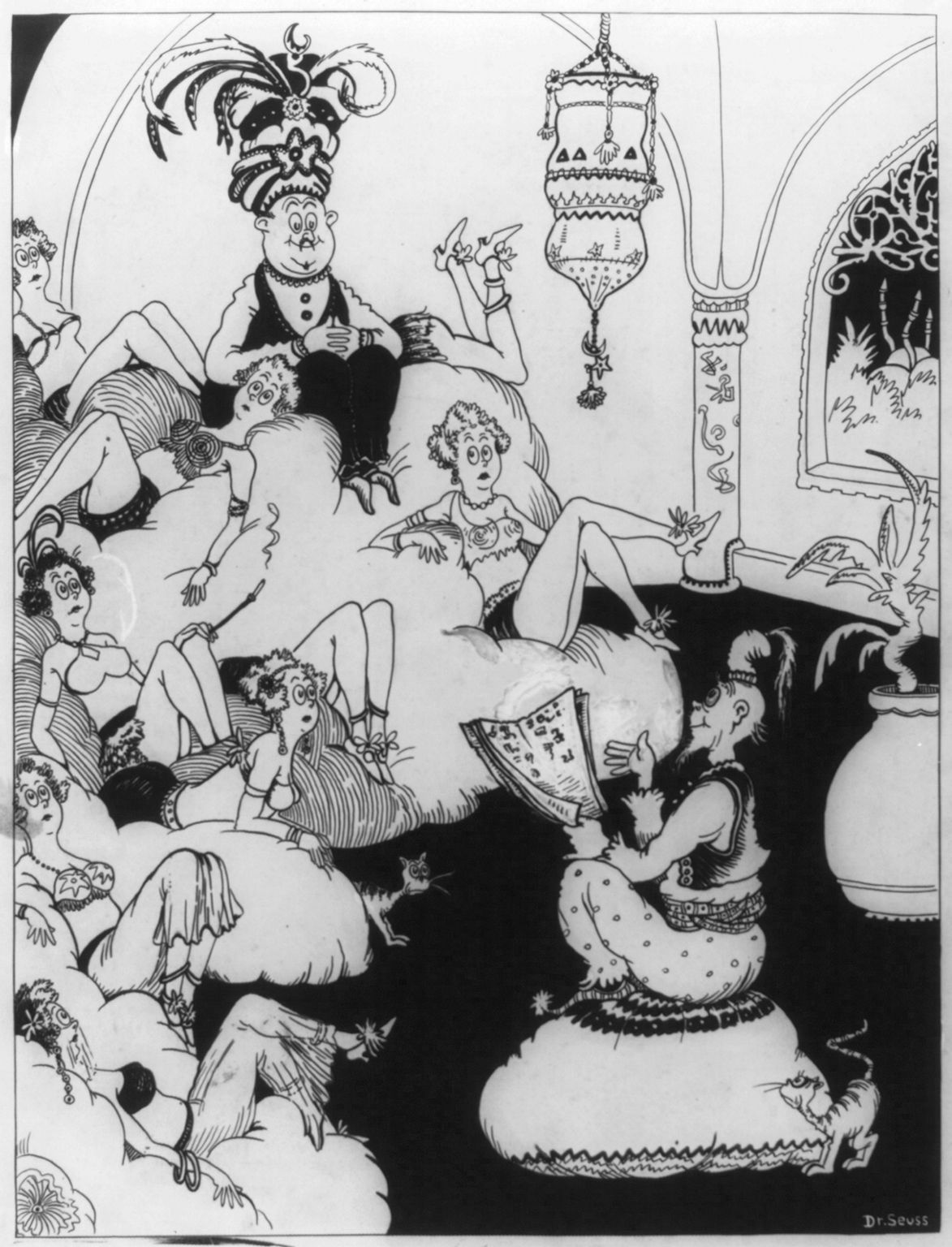

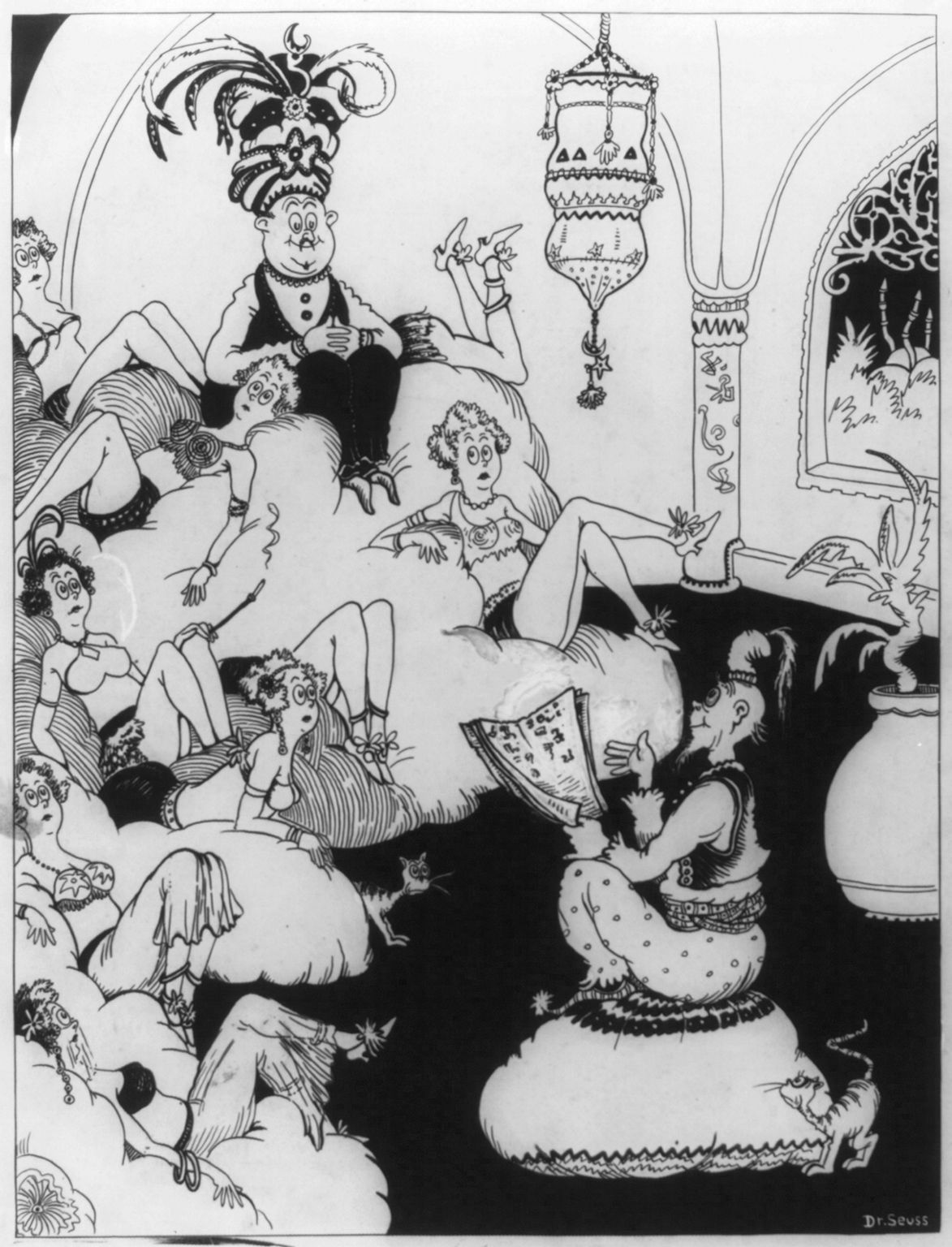

was perceived as fascist. Satirizing Soddy, Dr. Seuss

opined, "It says here, oh most exalted one, that under technocracy

one man shall do the work of many." (Seuss, 1933).

To this day, technological panacea has

been suspect. Whether Brautigan intended the irony or not, his

poem All

watched over by machines of loving grace does sound a bit

like an ad

for Cyberdyne Systems in the movie The Terminator. But isn't

a form of mechanized technocracy already in place, enabling one

man to do the work of many, and isn't that the root of our current

unemployment? Does

capital fail to keep labor relevant? Does market

shortsightedness squelch creativity and prevent our scientists

and engineers from focusing on the most pressing sustainability

issues of the day? Is

capital going to create or obstruct a green economy? If not

pro rata, would a market economy be better served with an energy

currency?

Ironically, the "energy certificates" of

the technocracy movement are not far from the concepts of energy

accounting in ecological

economics. Though perhaps anathema to some

environmentalists, tradable "cap allowances" are nothing but

inverses of "energy certificates." Both an energy certificate and

a cap are like a ration, the former a form of a paycheck allowing

energy consumption and the later a form of regulation limiting

entropic energy dissipation. The difference is that they are

equated into the same unit of measure, and are thus tradable. What

good is it to the environment if you carpool, ride the bus or

train, or bike commute only to be passed by a Hummer with a set of

rubber testicles hanging from the back bumper? Let them have their

freedom of self expression, but make them pay for any of its

excesses, and reward yourself by selling them a cap-allowance you

conserved equal in energy terms to your energy-based pay.

The key to any ecologically sound, energy

based economy is to recognize the value of the natural environment

in energy terms, and not just GDP. In a 1997 article in Nature, Robert

Costanza, current Director of the Gund Institute for Ecological

Economics at the University of Vermont, attempted to total

the value of "ecosystem services" in today's economic measure,

money. Though not without his critics for reducing the environment

into commodities, he showed that the economic value of the

environment can no longer be taken for granted. Is Costanza the

economical Lorax? Would Dr. Seuss approve?

We come full circle to the moral

vexations embedded in sustainability. In 1798, an Anglican

clergyman, Thomas

Malthus, first elaborated the grim calculus that arithmetic

increases in food production could not keep pace with geometric

increases in human population. A chapter in his An

Essay on the Principle of Population reviewed a sobering

list of the mechanisms that limit human population,

including famine, disease, and war. Although his predictions of

widespread famine have failed to materialize, human

population did not reach its first billion people until the

1880's. At that time, agriculture was already extended beyond the

natural rates of production by the mining of ammonium-nitrate

fertilizer, but still limited by the availability of these natural

deposits, most notably the mined saltpeter in

Chile's Atacama Desert. In 1909, Fritz Haber developed a method

for which he won the 1918 Nobel Prize in chemistry: the industrial

synthesis of ammonia using atmospheric nitrogen and hydrogen, the

hydrogen originally produced from the electrolysis of water.

Ammonia, like many high energy nitrogen compounds, had military

value in the making of explosives. With the advent of World War I,

and with the strategic Chilean deposits in British hands, Haber's

ammonia production went into making explosives, and Haber

himself went into making chlorine gas chemical weapons.

After the war, ammonia production was once again focused into

making fertilizer. Eventually natural gas became the principal

source of hydrogen, and, as Manning elucidates, an energy path

from the oil fields to the farm fields was established. In the

short 100 years since the development of the Haber process, along

with other technological agricultural methods of the Green

Revolution, the world has added another five billion people.

Is this growth sustainable?

Malthus was criticized in his day for his

audacity, daring to challenge the assumption of providence. In

more recent times, Paul Ehrlich predicted famine and advocated

population control. Like Malthus before him, his 1968 epic, The Population Bomb overstated predictions

of worldwide famine, but he rightfully points to famine in the 3rd

world as proof that the natural carrying capacity of the region is

exceeded even if the cause of the famine is political. Is Ehrlich

or Malthus proved wrong if the war, disease, and famine–the

dying–occurs only in the 3rd world, for political reasons, out of

sight and thus out of mind? In 1974, Garret Hardin proposed his

"lifeboat ethics," suggesting rich nations refuse to help more

populous poor nations in times of famine, in order to prevent an

even larger famine in subsequent generations. His "ethic" was

roundly criticized primarily for neglecting the disparity of the

ecological footprints of rich versus poor nations. The U.S. is

still the breadbasket

of the world, but is slowly converting part of its

agriculture from growing food for humans to growing fuel for

SUV's. Is this a "lifeboat ethics," or a selfish ethics of

suicide, something that Hardin

himself advocated and followed?

Whether technological agriculture is

sustainable or not, the world's population growth is

unprecedented, and there's no denying the energy demand to create

its food. Manning's treatise on the energy imperatives to sustain

our industrial agriculture is not lost on certain Washington D.C.

think tanks. Has the issue of world sustainability been used to

morally justify U.S. energy security in the name of world food

security? Is such an example of moral relativity associated with

sustainability in the modern age? What's at stake ethically in

these types of questions is every major issue of the modern age.

Modern sustainability issues go beyond mere food supply.

In his book The

Hydrogen Economy, Jeremey Rifken

posited a tenet every bit as sobering as the Malthusian tenets:

"...society is organized around the continuous effort to convert

available energy from the environment into used energy to sustain

human existence."(2002, p. 46). Malthus, Soddy, Haber, Ehrlich,

Hardin, Rifken, Manning, and the like are merely messengers of

this sobering reality of sustainability. Hardin's Tragedy

of the Commons, the depletion of the life-sustaining

ecosystem by population, is surmountable only with energy. Thus

the moral quandaries are insolvable without energy. But perhaps

the vexations can be used to set the priorities of our newly

defined economy, and channel our own energies accordingly. For

example, the admission of the vexing truth, the real reason for

the war as acknowledged by Greenspan, can finally be used in

arguments about which energy sector is truly receiving the most

government subsidy. Energy is driving. Economics is only along for

the ride. Rifken goes on to quote Soddy's prescience: "[the laws

of thermodynamics] control, in the last resort, the rise and fall

of political systems, the freedom or bondage of nations, the

movements of commerce and industry, the origins of wealth and

poverty, and the general physical welfare of the race." (Soddy,

1912, p. 245).

As we shall see in the remaining parts of

this article, energy assets and disorder debits can be tracked by

the 1st and 2nd laws of thermodynamics, through systems,

surroundings, and a universal net sum, encompassed like a set of

matryoshka dolls. Sustainability is only possible if the total

disorder created by a life system on its surroundings can be

overcome with an outside source of energy, usually from the Sun,

ultimately shifting a universal net disorder onto the surroundings

of the solar energy system. That is the succinct scientific

statement of the goal of sustainability. Unless and until we reach

that goal, unless and until the total disorder created by the

human population can be overcome with a continuous source of

energy, population will be limited, either naturally by one or

more of the Malthusian tenets, or by some measure of population

control. Though science can guide, the issue is then no longer a

discussion of scientific or technological solutions, but rather

becomes one of ethics, rooted in discussions of environmental and

economic justice. The economies of the world attempt to organize

life's energy and the inherent value of goods and services

resulting from life's work. To do this with any semblance of

justice, the economic system must account for the energy debits of

entropy.